|

| Anyone wanting to understand the context of the industry that created Winehaven has to read two books by Frances Dinkelspiel, Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California, and Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California.

Hellman was Dinkelspiels’s great-great grandfather, credited with consolidating the California wine industry into a giant monopoly, the California Wine Association, which controlled 84% of California Wine production from a place called Winehaven in Richmond, California.

On March 3, 1901, the San Francisco Examiner ran the headline, “Hellman Controls the Wine Industry.” The article exclaimed, “Banker Hellman and his financial associates have obtained control of the California Wine Association and with it control of the viticultural industry in California.”[1]

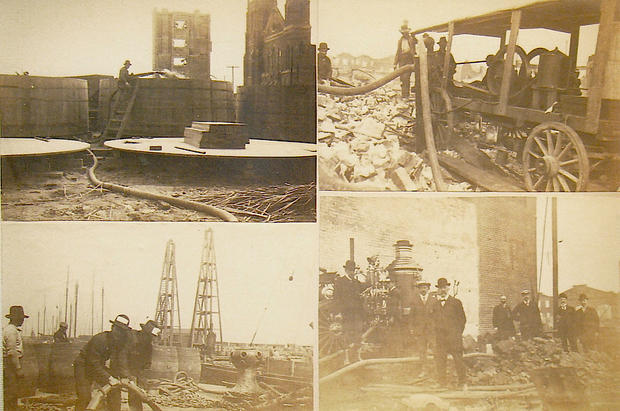

Five years later, the 1906 earthquake destroyed the seven San Francisco wine depots owned by the California Wine Association.

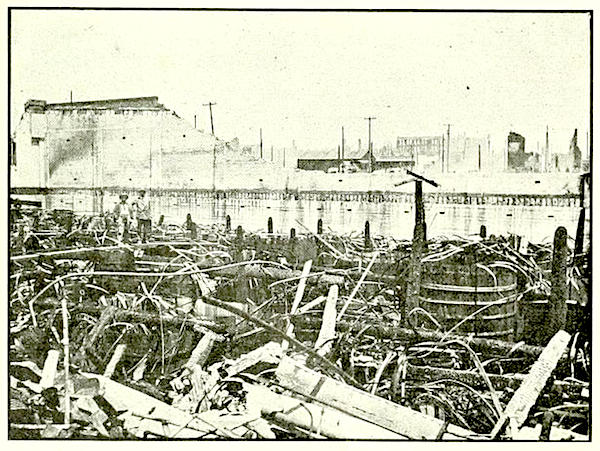

No one could have predicted this shattering holocaust. The earthquake and resulting inferno destroyed all but one of the Association’s San Francisco cellars…Of the estimated fifteen million gallons of wine destroyed throughout the city, ten million were in the cellars of the C.W.A and its associates…Amazingly, this devastating loss of wines and buildings did not trigger a collapse of the C.W.A. The firm, financially sound and adequately insured, was pronounced “in good shape” and paid the April 1906 dividend.[2]

Shortly after the earthquake, the Association purchased 47 acres in Richmond to consolidate their holdings into “Winehaven.”

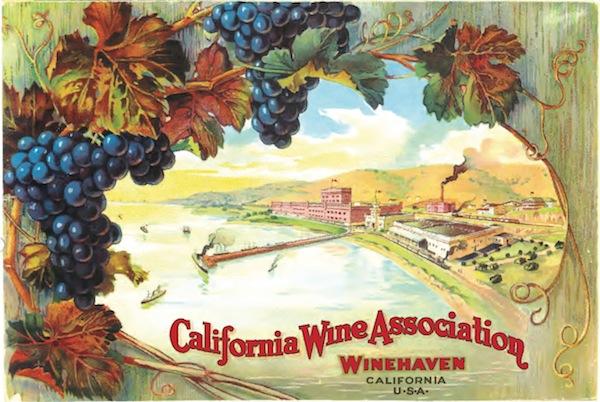

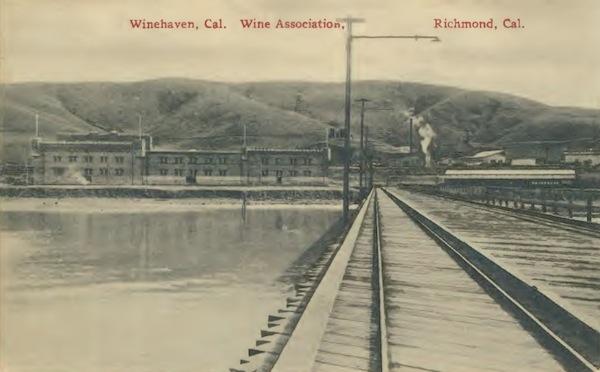

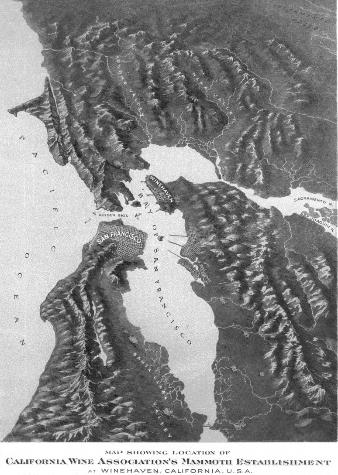

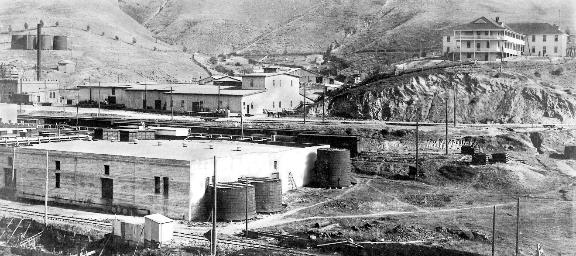

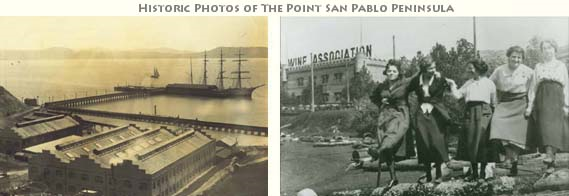

The immediate problem facing the Association was obtaining new wine cellars…[Percy]Morgan emphatically stated there would be no rebuilding of the San Francisco cellars. From the start-up of the Association, he had envisioned and planned for a consolidation of the seven San Francisco wine depots under one economy-saving roof. Now to this end, the Association purchased a forty-seven acre tract of land on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay, about four miles north of Point Richmond, and began work in late 1906 on the Association’s last and greatest enterprise, a company town “of a permanent nature” for wine production, storage and distribution – appropriately named Winehaven. They erected an immense ten million gallon capacity wine cellar of steel, concrete and red brick, and a fermenting cellar with an annual crushing capacity of 25,000 tons. The main building, also of sturdy concrete, easily accommodated offices, bottling facilities, shipping and receiving stations. The plant was complete – cooper shops, sherry ovens, by-product factories, and living quarters for employees and executives. Shipments were possible by rail or water. Winehaven was the largest and most up-to-date winery plant in existence.[3]

Winehaven, ultimately fell victim to Prohibition, but as late as 1919 there were two million gallons of grape juice stored there. The California Winegrowers Association never recovered, and Winehaven, its last major asset, was sold in 1941.

The two books provide a fascinating and lurid history of the California Wine industry and the role Dinkelspiel’s family played in it.

[1] Ernest P. Peninou and Gail G. Unzelman, The California Wine Association and Its Member Wineries 1894-1920 (Santa Rosa: Nomis Press, 2000) 93

2 Ibid, 104

3 Ibid 103-104

Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California (2010)

Isaias Hellman, a Jewish immigrant, arrived in California in 1859 with very little money in his pocket and his brother Herman by his side. By the time he died, he had effectively transformed Los Angeles into the modern metropolis we see today. In Frances Dinkelspiel's groundbreaking history, the early days of California are seen through the life of a man who started out as a simple store owner only to become California's premier money-man of the late 19th and early 20th century. Isaias Hellman, a Jewish immigrant, arrived in California in 1859 with very little money in his pocket and his brother Herman by his side. By the time he died, he had effectively transformed Los Angeles into the modern metropolis we see today. In Frances Dinkelspiel's groundbreaking history, the early days of California are seen through the life of a man who started out as a simple store owner only to become California's premier money-man of the late 19th and early 20th century.

Growing up as a young immigrant, Hellman quickly learned the use to which "capital" could be put, founding LA's Farmers and Merchants Bank, that city's first successful bank, and transforming Wells Fargo into one of the West's biggest financial institutions. He invested money with Henry Huntington to build trolley lines, lent Edward Doheney the funds that led him to discover California's huge oil reserves, and assisted Harrison Gary Otis in acquiring full ownership of the Los Angeles Times.

Hellman led the building of Los Angeles' first synagogue, the Wilshire Boulevard Temple, helped start the University of Southern California and served as Regent of the University of California. His influence, however, was not limited to Los Angeles. He controlled the California wine industry for almost twenty years and, after San Francisco's devastating 1906 earthquake and fire, calmed the financial markets there in order to help that great city rise from the ashes. With all of these accomplishments, Isaias Hellman almost single-handedly brought California into modernity.

Ripe with great historical events that filled the early days of California such as the Gold Rush and the San Francisco earthquake, Towers of Gold brings to life the transformation of California from a frontier society whose economy was driven by the barter of hides and exchange of gold dust into a vibrant state with the strongest economy in the nation.

Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California (2015)

On October 12, 2005, a massive fire broke out in the Wines Central wine warehouse in Vallejo, California. Within hours, the flames had destroyed 4.5 million bottles of California's finest wine worth more than $250 million, making it the largest destruction of wine in history. The fire had been deliberately set by a passionate oenophile named Mark Anderson, a skilled con man and thief with storage space at the warehouse who needed to cover his tracks.

With a propane torch and a bucket of gasoline-soaked rags, Anderson annihilated entire California vineyard libraries as well as bottles of some of the most sought-after wines in the world. Among the priceless bottles destroyed were 175 bottles of Port and Angelica from one of the oldest vineyards in California made by Frances Dinkelspiel's great-great grandfather, Isaias Hellman, in 1875. Sadly, Mark Anderson was not the first to harm the industry.

The history of the California wine trade, dating back to the 19th Century, is a story of vineyards with dark and bloody pasts, tales of rich men, strangling monopolies, the brutal enslavement of vineyard workers and murder. Five of the wine trade murders were associated with Isaias Hellman's vineyard in Rancho Cucamonga beginning with the killing of John Rains who owned the land at the time. He was shot several times, dragged from a wagon and left off the main road for the coyotes to feed on.

In her new book, Frances Dinkelspiel looks beneath the casually elegant veneer of California's wine regions to find the obsession, greed and violence lying in wait. Few people sipping a fine California Cabernet can even guess at the Tangled Vines where its life began.

Frances Dinkelspiel is an award-winning author and journalist. Her most recent book, Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California, is both a New York Times and San Francisco Chronicle bestseller. Her first book was Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California, which was also a San Francisco Chronicle bestseller. The San Francisco Chronicle and the Northern California Independent Booksellers Association both named it a Best Book of the Year. Towers of Gold was also a finalist for the Northern California Book Awards.

A graduate of Stanford University and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Frances started her reporting career at the Syracuse Newspapers in upstate New York and later moved to the San Jose Mercury News.

Frances’s freelance articles have appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, People Magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Magazine and elsewhere.

In 2009, after watching newspapers decimate their local reporting staffs, Frances co-founded Berkeleyside, a news site about Berkeley, CA. Berkeleyside has twice won the “Best Community News Site” award from the Northern California Society of Professional Journalists. In 2013, Frances and her partners created Nosh, a site about the food scene in the East Bay.

Frances is an accomplished speaker who has delivered more than 200 lectures on the history of California, Isaias Hellman, and the role Jews made to the development of the state. She has given talks at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, the Huntington Library, the Los Angeles Public Library’s ALOUD program, the San Francisco Public Library, the California Historical Society, the Contemporary Jewish Museum, the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, and elsewhere.

Frances has also appeared in a number of television shows and documentaries, including NBC’s genealogy show, “Who Do You Think You Are?” with Academy Award-winning actress Helen Hunt. She was also featured in the documentary, “American Jerusalem: Jews and the Making of San Francisco.”

In 2013, Frances received a Hess Winery Fellowship to attend the Napa Valley Wine Writers Symposium. She has also been a San Francisco Public Library Laureate and an honored author at the Berkeley Public Library Authors’ Dinner.

Frances was a faculty member in 2015 at the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley writing conference. She has also taught at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

Frances serves on the board of Litquake, the renowned literary festival in the Bay Area. She is the former president of the Judah L. Magnes Museum and Park Day School in Oakland, CA. She has also served on the boards of the Friends of the Bancroft Library, the Friends of the Magnes, and the Library Advisory Board for UC Berkeley.

Frances is a fifth-generation California who was born in San Francisco. She now lives in Berkeley with her husband, Gary Wayne, who works in the solar energy business. She has two adult daughters

The Forgotten Kingpins Who Conspired to Save California Wine

By Ben Marks

If you live in San Francisco and want to show off your knowledge of California wine to a few friends from out of town, you might take them to a wine-savvy restaurant like Boulevard, a block or so from the Ferry Building and San Francisco Bay. Scanning the multi-page wine list, you’d say something knowing about how hot Kongsgaard is right now, but you’d pass on the $165 bottle of its 2013 Chardonnay and order a $94 bottle of Far Niente—same varietal, same year—instead. Perusing the reds, you’d remark that the $650 price tag for a bottle of 2010 Sine Qua Non Stockholm Syndrome Syrah from the Santa Rita Hills of Santa Barbara County is actually quite reasonable, but that the 2010 Qupé Syrah from the nearby Edna Valley is also nice and, at $105, a bargain by comparison.

These recommendations would be sure to impress. But what if one of your old chums, rising to the challenge of your enological expertise, suddenly turns and asks if you know that the city of Richmond across the bay—home to a noxious Chevron oil refinery and is considered one of the 10 most dangerous cities with populations under 200,000—was once California’s undisputed wine capital?

You’d blink, and accuse your pal of pulling your leg, until he starts telling you the story of the rise and fall of the California Wine Association, which, in 1907, built a 47-acre compound there, evocatively named Winehaven.

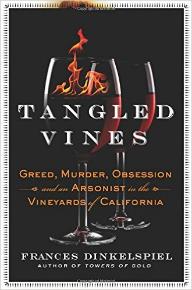

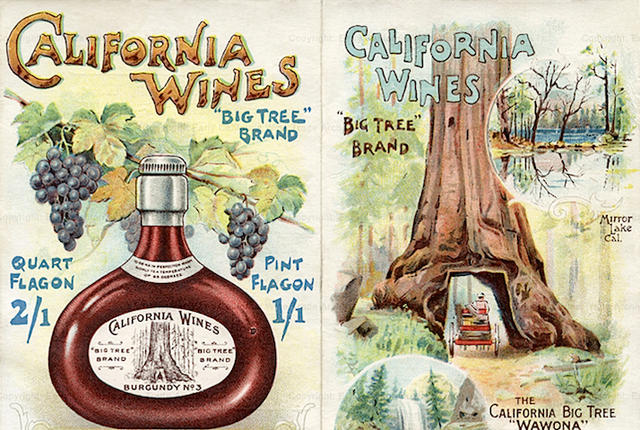

Top: In the late 1890s, the California Wine Association sold some of its members’ wine under the Big Tree brand. Click to enlarge. (Courtesy ofEarly California Wine Trade Archive) Above: A 1902 map touts the C.W.A.’s awards and geographic reach. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

The location was not a whim: In 1906, 10 million gallons of C.W.A. wine had been spilled in the San Francisco earthquake and boiled in the fires that followed. By the time your friend has finished explaining that as many as 12 million gallons of wine and brandy a year were once produced at Winehaven, you’d realize that while you may be able to order a decent bottle of wine in a fancy restaurant, you don’t know beans about California’s wine history, especially before Prohibition.

Few people do. In fact, if those who shop at BevMo for bargain bottles think about California’s wine history at all, their timeline usually begins in 1976 at the so-called Judgment of Paris, in which a Stag’s Leap Cabernet Sauvignon and a Chateau Montelena Chardonnay, both from the Napa Valley, stunned the international wine world by beating some of France’s most esteemed Bordeaux and Burgundies in a blind tasting.

To be sure, one would not directly credit the C.W.A. for the Judgment of Paris, but this watershed moment in California wine history didn’t come out of nowhere. Or at least that was my reaction after reading a terrific new book called Tangled Vines by Frances Dinkelspiel. Even though the main thread of Dinkelspiel’s narrative concerns the events leading up to an arson-caused warehouse fire in 2005, which destroyed 4.5 million bottles of wine worth at least a quarter-billion dollars, the story of the C.W.A.—at one point, it controlled a staggering 84 percent of California’s wine business—figures prominently. What else might Dinkelspiel know about the C.W.A. that didn’t make it into her book? My interest piqued, I decided to call her and find out.

“In the 1890s, the California wine industry was a mess,” Dinkelspiel told me when we spoke a few days later over the phone. The economic panic of 1893, she explained, had created a glut of grapes, severely depressing the price of fruit and wine alike. “The timing was right for someone to get in there and dominate the market in order to stabilize it,” she says.

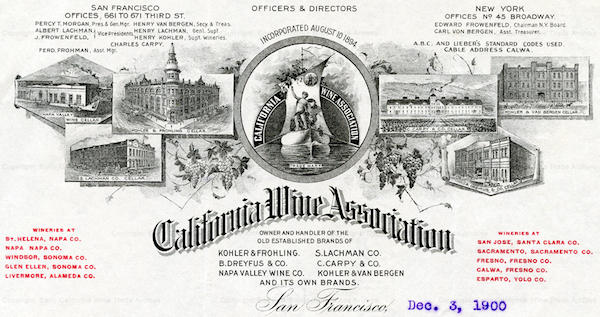

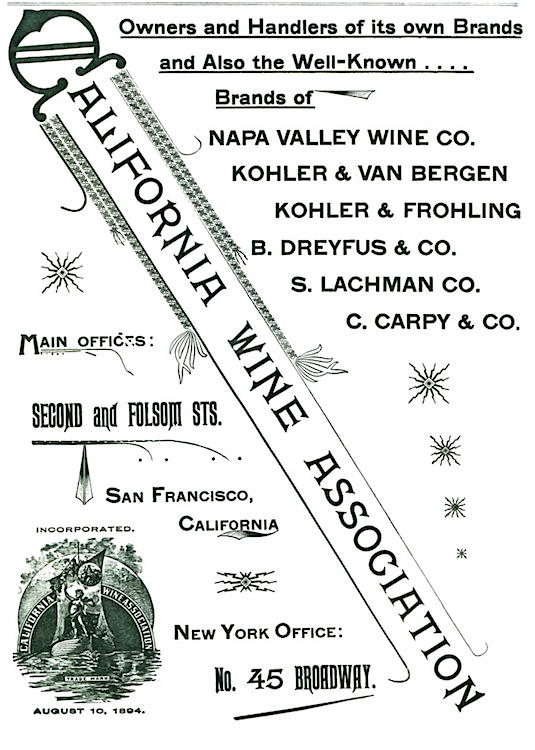

The C.W.A.’s letterhead from 1900, showing its warehouses in San Francisco and wineries throughout the state. (CourtesyEarly California Wine Trade Archive)

Founded in San Francisco in 1894, the C.W.A. was comprised of a number of highly influential “someones,” including the biggest and most successful wine merchants in the city, who had their hands in everything from the ownership of vineyards across the state to wineries and distributorships. By joining together to form the C.W.A., they were effectively colluding—in broad daylight—to create a wine cartel, despite the fact that the Sherman Antitrust Act had just passed in 1890. That’s how bad things were for California grape growers and wine merchants in 1894; the prospect of an antitrust lawsuit brought by the federal government was preferable to the status quo.

The main tactic of the newly formed C.W.A. was simple—wait everyone out. As the biggest buyer of California grapes and biggest seller of finished product, the C.W.A. could force growers to accept the prices it was willing to pay, lest they get nothing before their fruit rotted. Similarly, if wine sellers in Chicago, New Orleans, and New York didn’t want to pay the prices the monopoly was demanding for its barrels and bottles of wine, the association could simply hold onto its inventory until the recalcitrant wine merchants had run out of theirs.

Not surprisingly, such strong-arming did not sit well with growers, winemakers, and distributors not aligned with the C.W.A., which is why, by 1897, an all-out economic wine war was raging between the association and an upstart rival, the California Wine-Makers Corporation.

Because of its size and deep pockets, the C.W.A. had the upper hand on the economic battlefield. Under the leadership of president Percy Morgan, the association abandoned its 1893 tactics, which were designed to stabilize the wine market by holding the line on prices. Instead, it slashed the cost of its wine, undercutting Wine-Makers Corporation wineries. By 1900, that corporation’s three most important members, including the Italian-Swiss Colony winery of Sonoma County, had raised the white flag and joined the C.W.A. At the turn of the 20th century, membership in the C.W.A. was apparently the only way for a big California winery to survive.

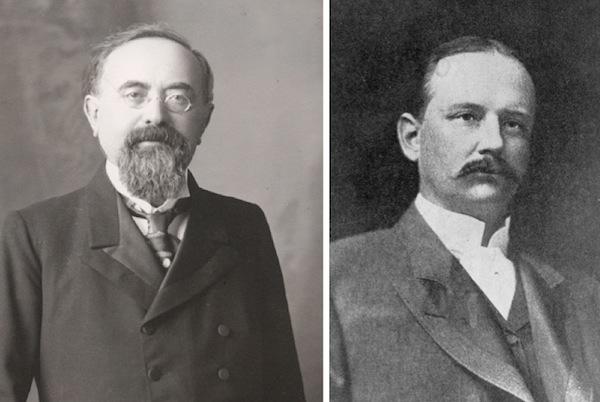

Two of California’s most important wine figures at the end of the 19thcentury were Isaias Hellmen (left) and Percy Morgan.

The resolution of this battle between the dueling cartels paved the way for an unprecedented $1 million investment in the C.W.A. in 1901. The equivalent of around $28 million today, the funding infusion was led by an investment banker and Southern California vineyard owner named Isaias Hellman, who just so happens to be Dinkelspiel’s great-great-grandfather.

Even without the family connection, the C.W.A. would have found its way into Tangled Vines. But Dinkelspiel’s page-turner had only whetted my appetite for details about the monopoly and the circumstances that led to its creation, so I called up wine writer and publisher Gail Unzelman, whose The California Wine Association and Its Member Wineries, 1894-1920, co-authored with the late wine historian Ernest Peninou, is considered the definitive work on the subject.

As a publisher of books via Nomis Press and a respected wine quarterly called “Wayward Tendrils,” Unzelman has provided a platform for such esteemed wine writers and historians as Peninou, Thomas Pinney, and Charles Sullivan. As a collector for more than 40 years, she’s filled binder upon binder with wine ephemera such as labels and wine-related postcards, as well as a wine library that now boasts some 4,000 titles, most of them focused on California’s viticultural history.

“I think it’s about 3,917,” Unzelman corrects me when we speak. “I’m a very organized person, and I can still get through my house,” she adds. “It’s not like there’s stuff in the hallway—yet.”

The C.W.A.’s logo featured Bacchus, the god of wine, sailing with a grizzly bear like the one on California’s state flag. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

One of the cornerstones of Unzelman’s book collection is a one-of-a-kind, handmade volume, which came to her almost by accident. “I was at an antiques show in Sacramento,” Unzelman recalls. “I asked a dealer there if she had anything on wine. She said, ‘No, not really, but I’ve got this old scrapbook here that’s got wine clippings in it.’ It was a nice scrapbook, leather-bound and very thick. It happened to be C.W.A. president Percy Morgan’s scrapbook.” The scrapbook sat in Unzelman’s closet with all her other binders and historical goodies for years, until Peninou came along with his draft of what became The California Wine Association and Its Member Wineries. “That Morgan scrapbook gave us a lot of information that wasn’t known at the time,” Unzelman says.

Unlike the board members of the C.W.A., who represented the crème de la crème of the California wine industry, Morgan was a money guy, which is to say he was an accountant, although his business card also bore a second, fancier title, “Financial Agent.” During the late 1880s, Morgan helped manage the financial affairs of such forgotten San Francisco firms as Nevada Gypsum & Fertilizer Co. and Pacific Auxiliary Fire Alarm Co., but in 1892, he gained a toehold in the world of wine by being named a director of the Samuel Lachman Estate Co., which managed the various holdings of the late Mr. Lachman, including his wine-merchant firm, S. Lachman Company. After their father’s passing, Samuel’s two sons aligned themselves with the C.W.A., turning over their two-million-gallon-capacity warehouse on Brannan Street in San Francisco to the association so it could store its wine there.

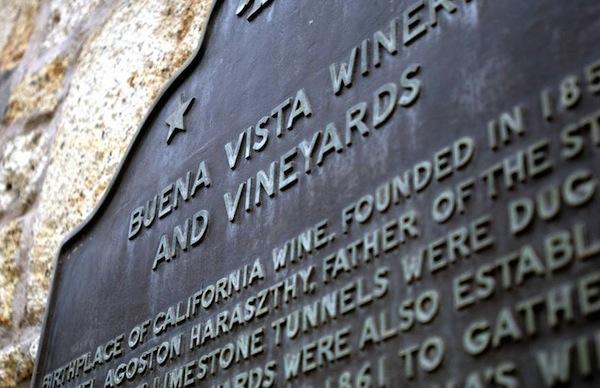

Buena Vista Winery in Sonoma may be designated as State of California Landmark number 392, but it is not the “birthplace of California wine.” (Via Buena Vista Winery)

Other than the Morgan scrapbook, it’s a safe bet that a good portion of Unzelman’s source materials overlapped with those Dinkelspiel studied at the Bancroft Library on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. There, she learned about her family’s wine lineage, beginning with her great-great-grandfather’s winery in what was once a dusty speck of a town east of Los Angeles called Rancho Cucamonga. Southern California is where the state’s wine industry began, despite a plaque at the Buena Vista Winery in the Northern California county of Sonoma, which identifies the 1857 site as State of California Landmark number 392 and the “birthplace of California wine.”

In fact, Southern California’s place on the wine-history continuum begins in 1769, when the recently sainted Franciscan Father Junipero Serra founded the first of 21 California missions, including the one at San Juan Capistrano in 1776, where grape cuttings from Spain were planted. A few years later, at Mission San Gabriel Archangel near present-day Los Angeles, the fruit was found to thrive.

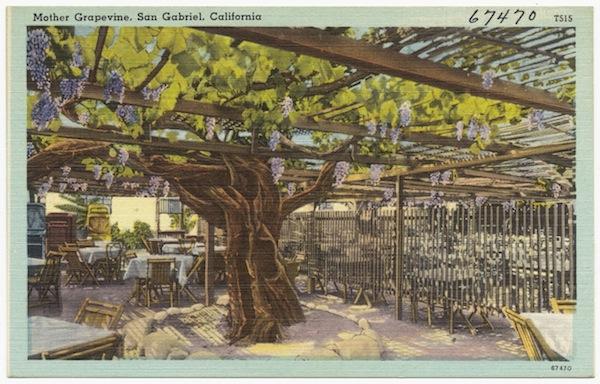

As Dinkelspiel describes it in Tangled Vines, the local Native Americans whose souls were supposedly being saved at Mission San Gabriel “were treated like slaves” by Father Jose Maria de Zalvidea, who directed them to clear 170 acres of chaparral-covered earth for row upon row of grape vines. “It was known as La Vina Madre, or the mother vineyard,” Dinkelspiel writes. “By 1829, the mission may have been producing from 400 to 600 barrels of wine a year.”

Author Frances Dinkelspiel in Rancho Cucamonga, where her great-great-grandfather Isaias Hellman once owned the winery founded by Tiburcio Tapia. (Via francesdinkelspiel.com)

A decade later, in 1839, a former Mexican soldier named Tiburcio Tapia planted even more Mission grapes at the Cucamonga Rancho, about 30 miles due east of Mission San Gabriel. Back then California was still a part of Mexico, so Tapia got his 13,000 acres directly from the Mexican government. Before long, the Cucamonga Vineyard, as it came to be called, covered more than 600 acres of the Rancho, making it a more accurate birthplace of the California wine industry. Sorry, Sonoma.

By 1848, California was a territory of the United States—statehood followed in 1850. After numerous changes in ownership, which Dinkelspiel covers in often bloody detail in Tangled Vines, in 1870, Isaias Hellman purchased the Cucamonga Rancho and Vineyard in a sheriff’s sale to settle various claims against the Rancho and satisfy its debts. It’s not known for sure if any of the grapes still growing at the Cucamonga Vineyard in 1870 had been taken directly from cuttings at La Vina Madre, but the character of the wine produced there was probably not markedly different from the sweet, sacramental stuff made for Serra and de Zalvidea.

The “Mother Grapevine” in San Gabriel, circa 1930-1945. (Via Digital Commonwealth)

This raises an interesting question: What did 19th-century California wine taste like, anyway? “It’s so undocumented,” Unzelman says. “I had a conversation recently with someone who was looking for tasting notes from that period, but they didn’t describe wine like we do today. They would analyze a wine and say it had good acid, that it was bold, that it was red. Sometimes they might say a wine was ‘velveteen,’ but they wouldn’t have said it had raspberry, blackberry, or cherry ‘notes.’ They didn’t talk about wine that way.”

Even so, we do have a few clues. To begin, we know that a sizable percentage of the wine produced in Southern California was fortified with brandy to lengthen its shelf life and increase its alcohol content. One type of fortified wine produced at the Cucamonga Vineyard before and during Hellman’s 40-year ownership of the property was port. Another was Angelica, which was actually an unfermented, fortified, grape-juice-based beverage rather than a wine per se—in wine circles, a blend of this type is called a mistelle.

If you could time-travel a bottle of Angelica from the Southern California of that era to a restaurant like Boulevard today, it would not make the wine list. This is not a guess. In the middle of the 19th century, the state’s wine was routinely sneered at by wine aficionados and, more importantly, wine merchants in New York, who also purchased wine from local sources in the eastern United States, as well as from European wineries. Before the transcontinental railroad was finished in 1869, California wine had to be shipped in “pipes” (large barrels holding about 125 gallons each) around South America’s Cape Horn.

A barge of California wine barrels being loaded onto a cargo ship in San Francisco Bay, 1912. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

Was it worth the effort? In 1862, a professional wine taster in New York dismissed what was considered one of the best Los Angeles-area Angelicas, made by Sainsevain Brothers, as follows: “A bottle full of it contains I don’t know how many headaches.”

With praise like that, it makes you wonder why Hellman was so keen to get his hands on the Cucamonga Vineyard in 1870. Dinkelspiel thinks she knows the reason. “I cannot speak to how much he loved wine,” she says of her great-great-grandfather’s motivations, “but he was very intrigued by the future of wine and agriculture. He was trying to make it a viable business.”

In 1901, therefore, the C.W.A. represented a new investment opportunity for Hellman in a familiar agricultural sector. Hellman may have had holdings and roots—literally—in Rancho Cucamonga, but he could plainly see that the industry was moving north. Sure, the Mission grapes that produced sweet, fortified wines like port did well in the south, but the climate was poorly suited to varietals that would produce the dry table wines that were becoming increasingly popular for daily drinking. Growers quickly discovered that counties like Sonoma and Napa were better for that. Sorry, SoCal.

Indeed, in 1870, the same year Hellman bought the Cucamonga Vineyard and its hundreds of acres of Mission grapevines at a sheriff’s sale, more visionary agricultural entrepreneurs were already planting neat rows of Zinfandel grapes in Sonoma. There, and on the other side of the Mayacamas Mountains in Napa, the seeds of the modern age of California winemaking were being sown, which perhaps accounts for the confusion of California’s official historians.

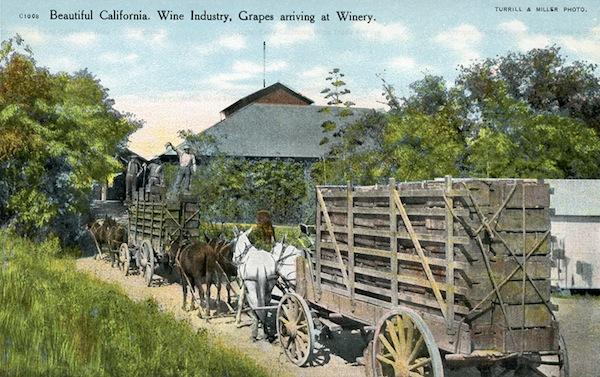

This is how grapes were brought in from the vineyards for processing in a Napa winery, circa 1905. (Courtesy Early California Wine Trade Archive)

The data tell the tale of this migration north. In 1858, more than 46 percent of all the grapes grown and harvested in California came from the Los Angeles Viticultural District, home to the Cucamonga Vineyard. That year, Napa and Sonoma combined accounted for less than 10 percent of the state’s total production. A decade later, though, the two northern California counties were on par with Los Angeles, and by 1890, Napa and Sonoma could claim more than 50 percent of the state’s total acreage in wine grapes, compared to less than 10 percent for L.A. Meanwhile, sweet-wine production was moving to the San Joaquin Valley. In short, Southern California no longer represented the future of California winemaking, and Hellman knew it.

As a businessman, you’d think Hellman might have balked at the idea of investing in an obvious monopoly, but according to Thomas Pinney in The Makers of American Wine, the C.W.A. “escaped attention from the Department of Justice,” because antitrust laws at the time applied only to staple commodities, which the C.W.A. successfully argued wine was not. Similarly, the independent wine firms that became a part of the C.W.A. remained independent in their management after being subsumed into the C.W.A., presenting a veneer of competition between allegedly autonomous members, even though no such competition existed in practice.

A C.W.A. ad in “Pacific Wine & Spirit Review,” late 1890s. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

But the most important salve against antitrust action, Pinney writes, was the policy of keeping retail wine prices reasonable—if there was no price-gouging, regulators were encouraged to reason, how bad could this so-called monopoly really be? In fact, low prices were fine if you were a consumer, but, as Pinney writes, it “was of no apparent concern” to regulators that “in order to maintain modest prices, it might be necessary to gouge the grape grower and the winemaker.” In fact, that gouging was exactly what precipitated the formation of the California Wine-Makers Corporation and triggered the wine wars of the 1890s.

Stabilizing prices turned out to be the simplest part of the C.W.A.’s job. Trickier was controlling its wines’ reputation, which, at the turn of the 20th century, largely meant changing the way wine was bought and sold. To this end, the C.W.A. encouraged the practice of only shipping wine bottled and labeled in California to cities in the Midwest and on the eastern seaboard, since shipping wine in bulk clearly invited fraud.

Here’s how it worked: Throughout the late 1800s, wine was routinely sold in large barrels known as pipes. Upon receipt of a pipe of perfectly good California wine, local wine merchants would often blend the liquid to suit their tastes. More notoriously, a pipe of eastern rotgut that a merchant may have been forced to acquire in a bulk purchase might be blended with a pipe of much better California wine before being bottled and sold with the local merchant’s “California-grown” label on it. Naturally, if a consumer bought a bottle of alleged California wine that left a bad taste in their mouth, they’d think twice before buying another, weakening overall demand.

This photo from the July 31, 1906, issue of the “Pacific Wine & Spirit Review,” shows the damage to the C.W.A.’s Fourth Street cellars caused by the April 18 earthquake. (Via archive.org)

The C.W.A. was just beginning to make headway on this ambitious goal of shipping only bottled wine when the San Francisco earthquake struck on April 18, 1906. Since its founding in 1894, San Francisco had been C.W.A.’s main base of business operations, the place where deals were struck and millions of gallons of wine was warehoused in sites across the city. After the ground stopped shaking, this geographic diversification looked like it had been a good idea since most of the C.W.A.’s structures survived. But then came the fires, which consumed most of the C.W.A.’s warehouses. According to Charles Sullivan in the April 2006 edition of Unzelman’s “Wayward Tendrils,” “Of the twenty-eight commercial wine establishments in the city, twenty-five were destroyed.”

The most famous C.W.A. survivor was the Italian-Swiss Colony cellar at Battery and Greenwich Streets near the San Francisco waterfront. It still stands there today, thanks to the Colony’s founder, Andrea Sbarboro, who directed employees to flood the warehouse’s roof with water pumped from a spring on the property. “We fought unceasingly for three days and three nights,” Sbarboro would later write of the battle to keep the fires raging around him from reaching the Italian-Swiss Colony building. Two million gallons of C.W.A. wine were saved.

In these photos taken by Percy Morgan, wine is pumped through fire hoses from C.W.A. headquarters at Third and Bryant Streets to tanks on an awaiting barge. Click to enlarge. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

Another two million were salvaged from the C.W.A.’s main headquarters, at Third and Bryant Streets, but not before “the wooden tanks and casks came apart in the fire storm,” as Sullivan describes it. The spilled wine might have washed into the streets as it had at other warehouses, but a “plugged sewer line” and the building’s solid concrete walls and floor kept the sloshing wine within the structure. Suddenly, the building itself had become a wine cellar, which enabled the C.W.A. to pump the precious liquid through fire hoses to a small fleet of barges, which were towed to Stockton in the San Joaquin Valley, where the wine was distilled into brandy.

That was an acceptable solution to a difficult circumstance, since the distillation process neutralized the contaminants in the spilled C.W.A. wine, but the marketing plan for 35,000 bottles of wine that had not been destroyed at Third and Bryant was a good deal sketchier. “These bottles were supposedly cased with a special label as a souvenir of the disaster,” writes a skeptical Sullivan in “Wayward Tendrils,” and the wine was advertised as having been “mellowed and ripened and aged by the heat,” a specious claim at best. “Of course this is a very expensive way to produce fine wines,” read another C.W.A. announcement, “and the Association will certainly not endeavor to repeat their success.”

In fact, Sullivan suggests these 35,000 bottles might never have existed at all, except perhaps in the overheated imagination of a public-relations flack. “I have never seen any such label,” Sullivan writes. “Neither have I read anything about their later release or heard a word from anyone who has ever seen one.”

Dean Walters hasn’t seen one, either, which is saying a lot since he was long the leading dealer of California wine ephemera. Today, Walters runs the Early California Wine Trade Archive and is working to create a museum to house his and a few others’ sizable collections. “We hope to find space in an existing institution to exhibit our materials in a gallery setting and safely archive our materials,” Walters says. “The intent is to have changing displays focusing on wineries, districts, or special subjects.”

This colorful postcard of Winehaven seems to promise sunnier days after the trauma of the 1906 earthquake and the fires that followed. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

One subject might well be Winehaven, which Percy Morgan set out to build almost immediately after the fires caused by the earthquake had died down—the association would battle its insurance companies, who refused to pay legitimate fire-insurance claims, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which finally ruled in its favor in 1910. Strategically located at Point Molate in Richmond, Winehaven allowed Morgan to consolidate the C.W.A.’s activities in one place, which he believed would be economically more efficient than having lots of warehouses spread all over San Francisco.

It was. The east side of San Francisco Bay, which lacked bridges at the time, was also closer to transcontinental railroad lines than San Francisco, while its rail-equipped deep-water dock anticipated the shipping lane that would open through the Panama Canal in 1914. In addition, the pier made it easy to offload grapes grown in Napa and Sonoma counties, which could be sent down the Napa and Petaluma Rivers and across the bay to Winehaven for the fall crush. Some 25,000 tons of grapes were crushed at Winehaven in 1907, and in 1908, workers handled 45,000 tons of fruit, producing more than 675,000 gallons of wine that year.

Beyond its winemaking, bottling, and storage capabilities, Winehaven offered C.W.A. members cooperage services to help replace the thousands of tanks, barrels, and casks that had been destroyed in the 1906 fires. The oak for such containers had come from Arkansas and Tennessee, but after the 1906 earthquake, suppliers in those states jacked up prices by 40 percent. Coopers at Winehaven, therefore, turned to good old California redwood, which meant wine-storage containers of all sizes could be built for less than half the cost of oak ones.

View of Building One at Winehaven today. Note the braces holding the brick turret in place.

Architecturally, the crown jewel of Winehaven was Building One, which was clad in brick and featured “crenelated parapets and turrets on the corners,” to quote Sullivan. Like the C.W.A.’s headquarters at Third and Bryant Streets in San Francisco, Building One’s floors and ceiling were made of poured concrete, further reinforced by an inner skeleton of thick steel posts and beams. This construction method proved quite durable, surviving several decades of hard use by the Navy, which converted Point Molate into a fuel depot during World War II, as well as the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, which flattened a freeway and ruptured a section of the bridge between Oakland and San Francisco.

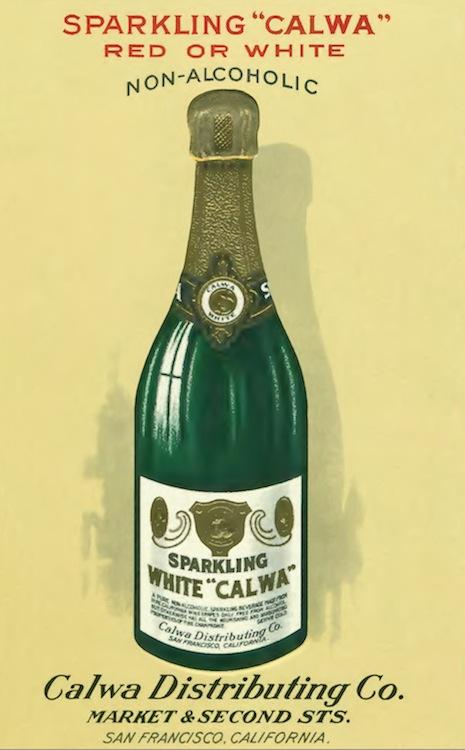

For Percy Morgan’s purposes, Winehaven was durable enough to help the C.W.A. solidify its hold on the California wine industry. By 1909, the Calwa Distributing Company was formed “to bring the consumer, in glass, the best wines of the California Wine Association,” as Peninou and Unzelman put it in their book. Calwa and Ca-dis-co became two of the C.W.A.’s biggest brands of “pure reliable wines,” as they were advertised.

Unfortunately, keeping the C.W.A. on its feet after the earthquake and during the construction of Winehaven had come at the price of Morgan’s health—by 1911, he would retire from the C.W.A. after 15 years at its helm, retreating to Europe for three years of “rest and recuperation” before returning home to serve on numerous boards (Stanford University among them) and build a three-story, half-timbered mansion south of San Francisco known as Morgan Manor.

Railroad tracks on the deep-water pier at Winehaven made it easy to load and unload the ships and barges that docked there. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

Despite Morgan’s exit from the C.W.A., the second decade of the 20th century began well for the association. “When the 1910 European vintage was virtually wiped out by bad weather,” Peninou and Unzelman write, “the California wine industry correspondingly prospered.” That’s one reason why, by 1913, the association was investing in numerous improvements and expansions at Winehaven.

At the same time, though, the C.W.A.’s future was cloudy. The association’s aging leaders were literally dying off, the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 had slowed exports, and, most ominously of all, the growing Prohibition movement in the United States suggested that it was only a matter of time before the C.W.A.’s very livelihood—selling alcoholic beverages—would be illegal.

In fact, the association first acted on the threat of Prohibition in 1907, when it began producing grape juice in earnest. By the end of 1909, the C.W.A. was selling both still and sparkling non-alcoholic grape drinks—produced in red (Zinfandel) and white (Muscatel) at a facility in the San Joaquin Valley—under the Calwa brand. “Calwa Grape Juice Steadies the Nerves,” promised one advertisement. The slogan may well have been a subconscious attempt to steady the nerves of C.W.A. officials, too.

As Prohibition loomed, the C.W.A. put more of its energies and resources into non-alcoholic grape beverages such as Calwa. (Courtesy Gail Unzelman)

Other C.W.A. actions betrayed more overt alarm. As early as 1908, the C.W.A. had been slowing its purchases of grapes from its growers, lest its inventories grow too quickly, and in 1909, it published a 62-page booklet promoting the enlightened ideal of temperance versus outright Prohibition, quoting Thomas Jefferson and St. Paul to make its case. Congress didn’t help matters when, in 1915, it raised the tax on the brandy used to fortify port and other C.W.A. products from three to 55 cents per gallon. And then, in 1916, the C.W.A. found itself fighting a pair of pro-Prohibition amendments on the California ballot, reprinting and distributing hundreds of thousands of copies of a booklet titled “How Prohibition Would Affect California” to help sway public opinion.

In the end, California voters rejected both measures, but this victory at the ballot box would not derail the Prohibition movement. Since the C.W.A. could see that it would not be long before Prohibition would become the law of the land, it began to rid itself of the millions of gallons of wine it had in storage at Winehaven. But 1917 was a very bad year to be selling wine. By the end of the year, Congress had passed the 18th Amendment banning “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors,” which was promptly sent to the states for ratification.

With the market for its goods soft at home, the C.W.A. looked internationally for buyers, but the war in Europe made exports to that region problematic, and even after war ended in November 1918, Europe was an economic shambles, making it a poor customer for California wine. One of the few bright spots in the C.W.A.’s efforts to liquidate its liquid assets came from former C.W.A. nemesis—and 1906 savior—Italian-Swiss Colony, which managed to sell 84,000 cases of its Golden State champagne into Asian markets for more than $1 million.

To combat the fraud that occurred when its wine was shipped out of state in barrels and pipes, which could be blended before bottling, the C.W.A. promoted the practice of shipping its wine in bottles. (Courtesy of Early California Wine Trade Archive)

All this made Percy Morgan, the man who had done more than anyone to make the C.W.A. the force it had become, inconsolable. On the morning of April 16, 1920, just three months after the passage of the Volstead Act, which put regulatory teeth in the 18th Amendment, the C.W.A.’s former leader, still in his pajamas, walked into the library of Morgan Manor, raised a shotgun to his head, and pulled the trigger.

Meanwhile, the increasingly desperate C.W.A. was trying to relocate its grape-juice business from the San Joaquin Valley to Winehaven, but this costly effort failed to generate the revenues needed to keep the enterprise afloat. As for its wine inventory, it was slowly sold as the law permitted—some export licenses were granted after Prohibition, and some of the liquid in the barrels at Winehaven was sold as sacramental wine, bringing the story of California’s wine history full circle.

As it turns out, a small amount of the wine stored at Winehaven may have been owned by the heirs of Isaias Hellman, who passed away from natural causes about a week before Morgan’s violent end. According to Frances Dinkelspiel, there were two types of Hellman wine that may have been stored at Winehaven at the beginning of Prohibition, port and Angelica, both made from Mission grapes that had been planted as early as 1839 by Tiburcio Tapia. The Hellman wine was not that old—it was crushed in 1875—and it would not be bottled until 1921, when a Santa Rosa company, Grace Bros. Brewing, purchased the C.W.A. name and remaining wine inventory at Winehaven.

“Joseph Grace was a family friend,” Dinkelspiel says. “I don’t know this for a fact, but I speculate that he found these barrels and bottled them up for the family. During Prohibition, there were a lot of restrictions on wine, but you could make and own a certain amount of ‘home’ wine. Anyway, that’s what I think happened.”

Dinkelspiel estimates that probably no more than 600 bottles of her great-great-grandfather’s wine were filled in 1921, about half in port and half in Angelica. One of Dinkelspiel’s cousins ended up with less than a third of those bottles, 175 of which were stored in the wine warehouse that was torched by an arsonist in 2005—the primary subject of her book—obliterating her most tangible connection to her family’s wine legacy. For Dinkelspiel, the warehouse fire was not just a juicy story, it was personal.

Winehaven advocate Bobby Winston on the roof of Building One.

After reading her book, gulping its chapters like so many glasses of Far Niente Chardonnay at Boulevard, I realized I needed to see Winehaven for myself. To that end, Dinkelspiel got me in touch with Bobby Winston, who owns a publication called “Bay Crossings.” In turn, Winston introduced me to Willie Agnew, who is the caretaker at Point Molate and the guy who actually showed us around, doing everything from leading us onto Building One’s sunny roof to unlocking the structure’s mysterious basement.

As I quickly learned, Winston is one of Winehaven’s biggest boosters. He believes the property, now designated as the Winehaven National Historic District, is a natural spot for thoughtful redevelopment, including a winery. After all, it’s got all that wine history going for it, plus unobstructed views across the bay to Mount Tamalpais in Marin, making it a natural future tourist destination. Having grown during its naval years, Winehaven now stands at 71 acres, which Winston believes make it big enough to support a variety of small businesses, whose rent checks would help pay for its upkeep, similar to the successful private-public partnership at the historic Presidio in San Francisco.

Today, Building One is still the most iconic structure at Point Molate. Walking the grounds, one can almost picture the site’s winemaking and naval history being told through interpretive displays and exhibits. Wandering inside the empty structure, one can equally imagine the rows of redwood casks, filled with millions of gallons of wine, that must have consumed this now-silent space. The bones of the building would probably support such tonnage still, but the unreinforced brick walls inside and out would be costly to bring up to code—the building’s signature brick turrets are currently held in place by wide rings of aluminum.

The inside of Building One features concrete floors and ceilings, with heavy steel framing throughout.

Making such band-aid reinforcements permanent, as well as figuring out which of the other remaining Winehaven structures are worth saving, would probably only be a small part of the cost of bringing new life to the historic site. Substantial infrastructure improvements would be required before the first glass of wine was poured in Winehaven’s first tasting room. According to a report prepared by Winston for Richmond’s mayor, Tom Butt, Point Molate lacks electrical power, which is why this section of bayfront is still dark at night—if you ever find yourself driving east across the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge after sundown, look to your left, and you’ll see what I mean.

Plumbing is also a major problem. All of the water to the area flows through a single 12-inch pipe, and there is no collection system to send sewage in the opposite direction. Finally, there’s the road, which is just a single lane in each direction, with little room on either side for widening. And while there’s an exit off Interstate 580 to Point Molate if you are heading west, eastbound visitors must navigate a tangle of poorly marked boulevards, drives, and avenues. All of which explains why Winston, despite his enthusiasm and affection for Winehaven, believes the process of figuring out what to do with the site is probably decades away.

The last two bottles of Frances Dinkelspiel’s stash of her great-great-grandfather’s wine. (Via francesdinkelspiel.com)

For her part, Dinkelspiel has Winehaven to thank for preserving those precious bottles of 19th-century Hellman wine, even if the bulk of her inheritance was torched by an arsonist in 2005. Fortunately, she kept a couple of bottles of Hellman in her home. By the end of Tangled Vines, curiosity about what’s in those bottles has gotten the best of her, so she determines to taste their contents with an expert whose palate is at least on par with that 1862 taster who had written off the best Angelica in Southern California as being little more than a bottle of headaches. In fact, Dinkelspiel found an individual whose palate is no doubt light-years more discerning, a master sommelier named Fred Dame.

As she tells it in her book, Dame is a tough sell at first, but eventually Dinkelspiel convinces him to let her bring her last bottle of her great-great-grandfather’s port to Dame’s home so they may taste it and let the chips fall where they may. In Tangled Vines, she describes the care Dame takes to break the wax seal from the top of the bottle, and the way he eases the corkscrew into the cork. It crumbles, but is still moist at the bottom, a good sign.

“Almost immediately,” Dinkelspiel writes, “a sweet aphrodisiacal scent filled the air. I was standing about four feet away from the bottle yet I could smell the Port’s fumes. The aroma, cooped up inside a bottle for ninety-three years, rushed out.”

The translucent liquid itself, she writes, is dark amber, “almost the color of the redwood it was once stored in.” And then Dame pours two glasses, and for the first time in her life, Dinkelspiel brings her great-great-grandfather’s wine to her lips. “I lifted my glass and let the Port swirl over my tongue,” she writes. “I wasn’t prepared for the intensity of flavor. Sweetness exploded over my taste buds, followed by a pleasant sharpness.”

“It has a wonderful old clay smell that I love,” she quotes Dame as saying. “It has almost a sour cherry quality to it, like cherries soaked in brandy,” Dame says, concluding with his much-anticipated verdict: “It’s phenomenal.”

Maybe that’s why Hellman invested in the Cucamonga Vineyard. And maybe, just maybe, that other Southern California Angelica, ripped to shreds by a grumpy New York taster in 1862, got a bad rap. “I’ve never tasted the Angelica,” Dinkelspiel says. “A family member who has tasted it said it’s very good. I do have one bottle of Angelica,” she adds. “I’m kind of tempted to open it one day, but I haven’t—yet.”

(Thanks to Frances Dinkelspiel, Dean Walters, Gail Unzelman, Bobby Winston, and Willie Agnew for their help with this story. To learn more about California’s wine history, pick up a copy of Tangled Vines, and be sure to visit Nomis Press and the Early California Wine Trade Archive.)

The view west from Winehaven; the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge is on the left, while Mount Tamalpais is on the right.

This article originally appeared on Collectors Weekly. Follow them on Facebook and Twitter.

Writer discovers California ‘Gold’ in banking ancestor Isaias Hellman

By Karen S. Wilson

Posted on Dec. 10, 2008 at 10:35 pm

"Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California" by Frances Dinkelspiel (St. Martin's Press, $29.95)

Searching for ways to deal with the current economic crisis, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson could take a cue from Isaias Hellman, banker, capitalist and California visionary. More than once during financial panics in the 19th century, when bank runs were a too-frequent and devastating occurrence, Hellman resorted to a dramatic ploy to restore calm and confidence. He stacked massive towers of gold coins on the counter of his Farmers and Merchants Bank in Los Angeles.

Half a million dollars in plain view "was a tonic," his great-great-granddaughter Frances Dinkelspiel writes in "Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California" (St. Martin's Press). It was a sight that stopped withdrawals cold and even attracted deposits. Everyone, customers and competitors, seemed to trust Hellman's faith that better times were ahead.

A grand gesture, his towers of gold represented not only Hellman's keen sense of the public psyche when hard times arose but his own confidence in the opportunities and resources of California. Hellman was an essential part, according to Dinkelspiel, of the generation that built the economic engines and defined the social institutions of California. In that role and company, Hellman was arguably the single most powerful and influential Jew in the United States from the last quarter of the 19th century until his death in 1920.

A fifth-generation Californian and Bay Area journalist, Dinkelspiel grew up with little knowledge of her illustrious ancestor. She discovered in the Hellman papers at the California Historical Society "every reporter's dream: an unknown story about a critical chapter in the country's history."

Sifting through extensive correspondence, ledgers, newspaper clippings and diaries, she realized that Hellman was a titan of his time, "California's premier financier" when the state shed its isolation and became an economic force.

She soon was on a seven-year quest to re-insert Hellman into California history and expand the record of Jewish immigrant success beyond Levi Strauss (who was just one of several pioneer co-religionists helped by Hellman to build unimaginable fortunes).

Hellman arrived in Los Angeles from Bavaria in 1859, a few months shy of his 17th birthday. Still more Mexican than American and with a population of less than 5,000, Los Angeles was home to maybe 150 Jews, almost all merchants who belonged to a handful of extended families. Accompanied by his younger brother,

Herman, and with less than $100 between them, Hellman went to work as a clerk in a cousin's store.

Within a few years, Hellman was buying his own store, developing commercial property in the center of Los Angeles and going into business with men "who considered themselves the problem solvers" of the region. Men such as John G. Downey, an Irish immigrant and former governor of California, were eager to capitalize on the sterling reputation and business acumen of the 29-year-old when Hellman invited them to become shareholders in the Farmers and Merchants Bank.

Farmers and Merchants proved to be the city's first successful financial institution. It also became Hellman's springboard to a West Coast banking empire that by 1915 had resources totaling more than $100 million. The crown jewel in that empire was the Wells Fargo Nevada Bank.

In 1890, Hellman was tapped to save the Nevada Bank, a San Francisco firm that counted the Southern Pacific Railroad among its biggest customers. When capitalist E.H. Harriman decided to spin off the banking business of Wells Fargo, he approached Hellman to take charge of merging two of the state's oldest establishments and creating one of the West's largest financial institutions.

While Hellman had family ties to New York and European capitalists (his brother-in-law was Meyer Lehman of the Lehman Brothers commodity house), the roots of Hellman's success were in his local connections. He persistently partnered with friends and neighbors, Jews and non-Jews, first in Los Angeles and later in San Francisco. As his success grew, he promoted California investment opportunities to Lehman Brothers and other prominent Jewish firms in the East and increased the wealth on both coasts.

As an investor, adviser and leader, Hellman extended his success and influence over several other major industries in California. He partnered with Collis and Henry E. Huntington to develop railroads and trolley lines in Los Angeles and San Francisco. He loaned Charles Canfield and Edward Doheny $500 to purchase the land where they sunk the first free-flowing oil well in Los Angeles.

Hellman was the largest shareholder in the Los Angeles Water Co., a private firm that developed the city's water system in the 19th century, and personally sold a $14.5 million bond issue for the Spring Valley Water Co. that supplied San Francisco. Having early in his career invested in vineyards, in 1901 Hellman took control of the California wine industry, standardizing the product and elevating the reputation of the industry around the world. In addition, he developed land all over Los Angeles County, owned property in San Francisco and built a vacation retreat at Lake Tahoe that eventually became a state park.

Hellman's influence on Los Angeles is still evident today. In an instance where capitalism and philanthropy met, Jewish Hellman, Protestant Ozro Childs and Catholic Downey donated 110 acres to the Methodist founders of USC. The land was in the center of the partners' subdivision at the southwest edge of the city. They also extended the trolley line they owned from downtown to the new campus.

Their generosity gave potential land buyers a destination and a convenient way to get there. The city had a university, and the partners saw their land triple in value.

Hellman helped create another L.A. institution when he advised Harrison Gray Otis to buy out his partner in the Los Angeles Times and then provided the $18,000 loan required to put the paper in Otis' hands. Otis' descendants, the Chandler family, sold the massive media company that evolved for $8 billion in 2000.

Hellman's leadership went beyond the world of finance and business. When Los Angeles' first synagogue was built in 1872, he was president of Congregation B'nai B'rith, now known as Wilshire Boulevard Temple. He served as a regent of the University of California for more than 30 years and endowed a scholarship fund still supporting students. He took a leading role in the recovery of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. Beneficiaries of his philanthropy ranged from Catholic orphans to World War I Jewish European refugees.

While unquestionably Hellman achieved the immigrant's dream of success and acceptance in America, there were times when he was the target of anti-Jewish sentiments and anti-Semitic behavior. He and his companies also were subject to the wrath of unionists and socialists, progressive reformers and even betrayal by family members. His wealth, influence and fame brought both friends and enemies.

In its plain sense, the biography of Hellman is a story of nearly unfettered opportunity to apply one's skills and realize one's ambition. The openness of the American frontier stood in stark contrast to the restrictions on livelihood and residency most Jewish Europeans left behind. At a deeper level, Hellman's story is a reminder that it took skill, ambition and connections to transform that frontier into part of the United States and create a state that today has a gross domestic product larger than all but eight countries in the world.

Jews were notably among the diverse contributors of those necessary ingredients, as they have continued to be, for example, the Stern, Haas and Goldman families in San Francisco and the Factor, Taper, Casden and Lowy families in Los Angeles.

To her credit, Dinkelspiel presents a well-developed and even-handed portrayal of Hellman and his extended family. The biography maintains a solid historical context in which to understand the perspectives, philosophy and values of a gilded-age capitalist. His German-American-Jewish sense of responsibility to family, community, customers, investors, competitors and the future comes through clearly. Through the vehicle of one man and his networks of family, friends and associates, the foundational place in California history of Jewish immigrants generally is illuminated, as well.

Well-researched and highly readable, "Towers of Gold" makes an important contribution to both the history of the Golden State and the history of Jews in America. It is a very strong case for the veracity of the volume's subtitle -- "How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California" -- demonstrating the key role of Hellman in the urban and economic development of California.

It also adds a fresh perspective on the Jewish immigrants from Central Europe who in the mid-19th century joined in the continental expansion of the United States and set down roots in emerging communities. As historian Kevin Starr has noted, frontier California was influenced by "Jewish values and sensibility" in ways unprecedented anywhere else in the nation.

Hellman's life and accomplishments illustrated that influence, and this biography brings attention to its still-unfolding consequences.

Karen S. Wilson is a doctoral candidate in history at UCLA and curator for the upcoming Autry National Center exhibition on the history of Jews in Los Angeles.

[1] Ernest P. Peninou and Gail G. Unzelman, The California Wine Association and Its Member Wineries 1894-1920 (Santa Rosa: Nomis Press, 2000) 93

|

|