|

| The proponents of Measure L – Rent Control and Just Cause – have accurately identified a problem: Residential rents in Richmond, as elsewhere in the Bay Area, have outstripped the traditional measure of many renters’ ability to afford them. If rent exceeds 30% of a renter’s income, it is widely accepted to be excessive and unaffordable. In a mature economy, the balance between supply and demand for housing is supposed to result in that magic 30% rate.

But in the Bay Area, new jobs have far exceeded the supply of housing to accommodate workers, hence the escalation of rents. However, rent control is like swatting flies with a sledgehammer. You may get a few, but the collateral damage makes the effort questionable, and a lot will get away.

To work at all, Rent Control and Just Cause must go together. The basic argument for Just Cause is to stop a landlord from arbitrarily using an otherwise legal eviction action to create an opportunity to raise rents. The whole premise of Rent Control and Just Cause is based on the theory that landlords are inherently greedy and unscrupulous and must be prevented from raising rents beyond what is required to obtain a reasonable return on their investment. Just Cause essentially turns a month to month rental into a lifetime lease with guaranteed maximum annual increases.

Here are the top five reasons Rent Control and Just Cause won’t work:

1. History of Failure. Rent Control has never worked. Bay Area cities such as San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley and San Jose have had some version of rent control for decades and now have the highest rents and/or the fastest rising rents in the United States. Why would we embrace a policy that has a consistent record of failure? “Economists oppose rent control almost as unanimously as climate scientists oppose attempts to deny the reality of client change. 93 percent of economists (including liberals like Paul Krugman) agree that ceilings on rents reduce the quantity and quality of housing. And economists' views seem borne out by experience: most major cities with rent control (such as New York and San Francisco) tend to have very high rents, indicating that rent control is perhaps not functioning as effectively as its creators had wished. And yet urban planners and citizen activists are much more closely divided. What do they not understand?” (The Economics of Rent Control) Also see: Rent control isn’t solving California’s housing problems, The High Cost of Rent Control and Do rent controls work?

From the East Bay Times: But does rent control work? Christopher Palmer, an assistant professor who studies real estate at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, says it’s a “patch” solution that doesn’t solve the root problem: The region just hasn’t built enough housing to accommodate the influx of new people. “It just keeps it from getting worse for those who are lucky enough to get into a rent-controlled unit and helps them stay there,” Palmer said. “The way I see it, we’ve had this affordability crisis, 30 to 40 years in the making, and the solution of rent control is to have landlords pay for getting us out of that mess.”

2. Unintended Consequences. Rent Control and Just Cause end up hurting the very people they are intended to help the most and benefitting people who do not need help. This is counterintuitive but proven. In any rental market, there is turnover that, even with rent control, enables landlords to reset rents to market rates. In Berkeley, 80% of rent controlled units are at market levels (Berkeley Mayor Tom Bates criticized for encouraging landlords to form PAC). The maximum number of renters who benefit from rent control are those who qualify at the onset of the program, but from thereon, the number is steadily reduced over time until it stabilizes at maybe 20%, based on Berkeley’s experience. Of the approximately 30,000 rentals in Richmond, 21,000 are exempt from rent control by Costa Hawkins because they are single-family or constructed after 1995. Of the remaining 9,000, all but 1,800 will soon migrate to market levels due to turnover.

Rent Control and Just Cause provide a disincentive for landlords to rent to anyone with even a hint of potential issues, favoring people with stellar references, steady jobs, higher incomes, no pets, no children and no problems. The profile a rent-controlled landlord seeks out is a single, white female with no children and a good job. In 2002, the San Francisco Rent Board commissioned an extensive Tenant Survey of rent control in San Francisco. What they found may be surprising to proponents of rent control, and demonstrates a disparate impact that is at odds with the rhetoric of its proponents. According to that survey, in 2002, 72% of the inhabitants of rent controlled units in San Francisco were white, while 54% of those in market rate units were white. Slightly more men lived in San Francisco in 2002, but women made up the majority of tenants of rent controlled units. Although the 2000 Census showed that 20% of San Franciscans were disabled or had chronic illness, only 14% of tenants in rent controlled units were disabled or had chronic illness. In terms of family size, rent controlled units were much more likely to have a single resident than market rate units – 41% of rent controlled units were occupied by a single occupant, while only 29% of market rate units had a single occupant. While 21% of all rental units in San Francisco had children under 18 years old, only 13% of rent controlled units had children under 18. While 7% of market rate units were occupied by a single parent with children, only 2% of rent controlled units were occupied by a single parent with children. Seniors were also less likely to live in rent controlled units: While 15% of all units had at least one senior citizen living there, only 13% of rent controlled units had at least one senior living there. In terms of occupation, 48% of all in San Francisco renters claimed “management, professional, and related” jobs, while 62% of rent controlled tenants claimed the same. The story this data tells – notwithstanding the divisive emotional argument over about who cares more about tenants -- is a disparate impact: that rent controlled units tend to go to those who are:

a. White

b. Female

c. Single

d. Lack disability

e. Don’t have children

f. Are not seniors

g. Have good jobs

Other unintended consequences include a reduction in the rental stock due to conversion of single family rentals to owned rentals to avoid just cause and reduction in Section 8 units for the same reason. Although rent control advocates argue that due to Costa Hawkins, rent control does not discourage new apartment construction, they gloss over the disincentive that just cause provides for potential apartment investors. Richmond is already a poor market for rental housing investors because of its record low rents.

Just cause, which is intended to protect renters, can also do just the opposite, making it difficult, if not impossible, to evict problem renters, the ones who are dealing drugs, making too much noise or otherwise making their neighbors’ lives miserable .Although such behavior may technically constitute “just cause” for eviction, it has to be proven to the rent board, and experience in other cities has proven that neighbors are reluctant to provide the necessary witness testimony due to fears of reprisal or simply not being able to make time available to participate in a formal hearing.

Finally, rent control provides a disincentive for apartment owners to invest in maintenance and improvements for their property, since such recovery may be impossible at worst or involve extensive documentation and hearings before the Rent Board at best.

Aside from this particular ordinance being especially poorly-drafted and ill-conceived (and the economic effects that it will have on Richmond), is this really what we want to see in Richmond? See How the Rich Get Richer, Rental Edition and No, rent control does not work — it actually benefits the rich and hurts the poor.

3. Poorly Drafted. As an initiative, Measure L was drafted by a small group of zealous rent control advocates with tunnel vision without the public process and debate that would have benefitted an ordinance drafted by the City Council. As a result, it pushed the envelope of the radical extreme while embracing fatal flaws and litigable ambiguities that a more public process would have exposed and corrected. For example, in an effort to make the Rent Board as independent as possible, it gives it full control over its own budget with no checks, balances or controls. Although Just Cause is intended to address rentals not subject to Rent Control by the Costa Hawkins exemption, a landlord could still increase a rental rate to a level the renter could no longer afford and then exercise an eviction based on non-payment of rent. These cannot be corrected by the City Council; only another election can do the job. Why did the RPA and its allied organizations do it this way? They could not live with the compromises that might have occurred in a more public process.

4. New Bureaucracy. The authors of Measure L acknowledge that it is modeled after Santa Monica’s rent control and just cause organization, which has an annual budget approaching nearly $5 million and employs more than two dozen people. Berkeley’s rent control apparatus is about the same. That would make it Richmond’s fifth largest department, exceeded only by Police, Fire Public Works and, barely, the Library and Cultural Services. While the unit is intended to be supported by fees on landlords, the cost in, terms of time and effort, may be difficult to fully recover and thus would affect the general fund, taking resources away from existing priorities.

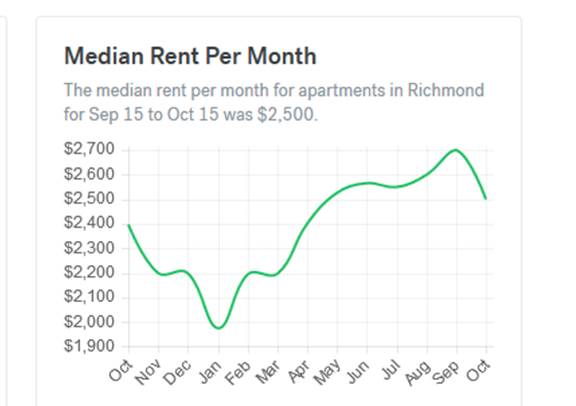

5. Rents Trending Downward. The basic premise for rent control and just cause is that rental rates are rising faster than inflation. It would have been impossible to make a case for rent control in Richmond between 2001 and 2011 when rents were stable or falling. It appears that rents not only in Richmond, but in most of the Bay Area have once again stabilized or are falling. Rent Control and Just Cause are not going to roll back rents to 2009 levels. If rents are now stable or falling, you have to ask yourself why we need a $5 million bureaucracy to do what the market is doing naturally? In any event, Richmond still has the lowest rents in the inner Bay Area.

https://www.trulia.com/real_estate/Richmond-California/

Bay Area rents are falling, falling, falling

http://www.mercurynews.com/2016/10/24/bay-area-rents-are-falling-new-survey-shows/

By Richard Scheinin / October 24, 2016 at 12:10 PM

AddThis Sharing Buttons

Share to Facebook1.2KShare to TwitterShare to LinkedIn62Share to RedditShare to FlipboardShare to Google+

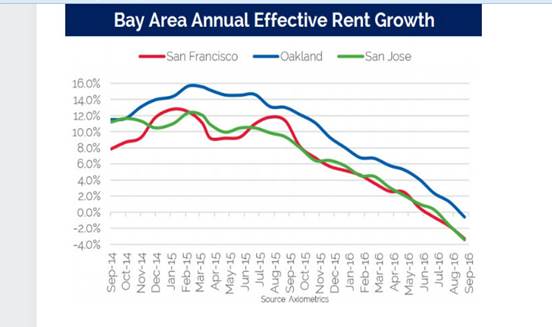

The message is becoming increasingly clear: Rents indeed are falling around the Bay Area.

New data from the Axiometrics research firm show rents dropping in San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland. The Oakland piece is a new twist; according to other surveys, Oakland rents have remained on the rise, though at a far slower rate than over the past year or two.

Here’s what Axiometrics has to say about average rents falling into “negative-rent-growth territory”:

- In September 2016, San Jose rents fell year over year by 3.4 percent from $2,814 in September 2015 to $2,718.

- During the same time period, San Francisco rents fell year over year by 3.3 percent from $3,336 to $3,226.

- And Oakland rents fell year over year by 0.6 percent from $2,392 to $2,378.

There were slight month-over-month declines between August and September 2016, as well: Rents dropped from $2,800 to $2,718 in San Jose (off 2.9 percent); from $3,301 to $3,226 in San Francisco (off 2.3 percent); and from $2,413 to $2,378 in Oakland (down 1.5 percent).

Now compare our region’s scenario to the nation’s: The average national rent stood at just $1,290 in September 2016, up year over year by 2.6 percent from $1,258, according to Axiometrics.

The Axiometrics study follows one by Abodo, the apartment search website. It showed rents dropping 7 percent between September and October in San Jose (from $2,455 to $2,293) for a one-bedroom apartment, and falling 6 percent in San Francisco (from $3,698 to $3,483). However, it showed rents still climbing in Oakland — by 5 percent, from $2,256 to $2,358 for a one-bedroom.

According to a third-quarter report by Novato-based RealFacts, the average San Jose apartment now rents for $2,500, up 0.6 percent from the third quarter of 2015, while the average San Francisco rent fell year over year by 3.4 percent to $3,499. In Oakland, the average rent is $2,927, according to RealFacts — up 2.8 percent on a year-over-year basis.

One last thought: Even though the runaway market is finally starting to cool off, most middle class folks still struggle to afford an apartment here.

Photo at top: A new crane rises up in downtown San Jose on May 18, 2015 for a seven-story apartment complex under construction at 51 N. 6th Street. (Karl Mondon/Bay Area News Group)

Will Bay Area rent control measures stop housing crisis? http://www.eastbaytimes.com/2016/10/21/rent-control-measures-hit-bay-area-ballots/

Linda Weinstock, left, and Angela Hockabout, founder of the Alameda Renters Coalition, participate in a rally at City Hall to protest rent increases in Alameda on Oct. 1, 2015.

By Tammerlin Drummond | tdrummond@bayareanewsgroup.com and Jason Green | jason.green@bayareanewsgroup.com

PUBLISHED: October 21, 2016 at 6:00 am | UPDATED: October 25, 2016 at 1:44 pm

A tenant movement has been gathering steam in the Bay Area, turning rent control into a hot-button political issue for the first time in decades.

On Nov. 8, voters in Alameda, Richmond, Mountain View, Burlingame and San Mateo will decide whether to enact new rent control proposals. In Oakland, where there is already a law, Measure JJ would impose new regulations limiting landlords’ ability to increase rents and expand just-cause eviction protections.

The outcome of this flurry of measures could significantly affect future rental policy. There are two questions at stake. One, is rent control an effective tool for addressing the state’s housing crisis? And second, is it fair for city officials to make a certain category of property owners shoulder the financial cost? By state law, cities can only limit annual rent increases on apartments built before Feb. 1, 1995. The Costa-Hawkins Rental Act also exempts all condos and single-family homes from rent control.

“It’s really historic,” said Leah Simon-Weisberg, legal director for Tenants Together, a statewide tenants-advocacy group that has been mobilizing support for the measures. According to the group, the new laws, if passed, would cover more than 100,000 people living in 52,000 apartments.

The measures sponsored by tenant advocates would limit annual rent increases based on the Consumer Price Index. In Alameda and Mountain View, city officials have put forward dueling rent-stabilization measures that do not set caps but instead require landlords to go through a new bureaucratic process if they want to raise rents higher than 5 percent.

Rent control supporters say it’s vital that the measures pass to protect low- and middle-income tenants from steep increases that are driving out longtime residents. They say rent control is something cities can do now to stanch the bleeding and give residents relief from the stress of being in constant fear of losing their homes.

“The working class and huge populations of color would be driven out of the Bay Area very quickly without rent control,” said Daniel DeBolt, a volunteer with “Yes on Measure V” in Mountain View. “It’s the one thing that stands between the displacement epidemic getting much much worse.”

Yet the California Apartment Association, which has spent more than half a million dollars to defeat the proposals, argues that expanding rent control only makes things worse.

“People will move into a rent control apartment and stay there for many, years and stay there for far longer than they need to as their family and income grow,” said Joshua Howard, CAA’s senior vice president of local public affairs. “That takes that unit off the market and constricts the supply of available housing as you’ve seen in Oakland, Berkeley and Santa Monica.”

The CAA cites the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office to back its claims. The February 2016 LAO report, titled “Perspectives on helping low-income Californians afford housing,” stated in part that proposals to expand rent control would likely discourage new housing construction and could lead to property owners cutting back on making repairs.

Tenant activists accused the CAA of putting out what they described as a deceptive mailer with the Legislative Analyst’s logo on it to mislead voters into thinking the agency had taken a position on the specific ballot measures — which it has not. Tenant groups picketed outside the CAA offices in Hayward, but the landlord group says it stands by the mailer.

Catherine Pauling, a spokeswoman for the Alameda Renters Coalition, said renters’ groups are being vastly outspent by deep pocketed landlord groups.

“Talk about David and Goliath. They’ve got all these TV spots running and robo calls,” Pauling said. “We’re really focusing on phone banking and going door to door.”

Melvin Willis, a community organizer with Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, helped collect signatures for Measure L, in Richmond, where he says tenants desperately need protection from unjust evictions.

“We’ve worked with tenants who’ve gotten $300 rent increases in rat trap buildings,” said Willis, a City Council candidate, “but they’re afraid to ask for repairs because they don’t want to get evicted.”

But does rent control work?

Christopher Palmer, an assistant professor who studies real estate at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, says it’s a “patch” solution that doesn’t solve the root problem: The region just hasn’t built enough housing to accommodate the influx of new people.

“It just keeps it from getting worse for those who are lucky enough to get into a rent-controlled unit and helps them stay there,” Palmer said. “The way I see it, we’ve had this affordability crisis, 30 to 40 years in the making, and the solution of rent control is to have landlords pay for getting us out of that mess.”

The East Bay Rental Housing Association, a group of landlords and property managers fighting Oakland’s JJ, said it places undue hardship on smaller landlords whose expenses are outpacing the amount they can collect under rent control.

“They’re just piling more and more on the property owners, and this is the frustration,” said Wayne Rowland, EBRHA’s president.

The outcome in each city will depend upon how many renters turn out to the polls. Homeowners usually vote in greater numbers.

“I realize it’s not a perfect solution,” said San Mateo Vice Mayor David Lim. “There are plenty of good, decent landlords who want to do the right thing, but when you’re facing families being displaced, kids being moved out of schools, people not being able to live in their community, it’s an easy choice for me.”

Rent control measures:

Oakland JJ

Would amend the Just Cause For Eviction and Rent Adjustment ordinances by extending just-cause eviction requirements from residential rental units offered for rent on or before Oct. 14, 1980, to those approved for occupancy before Dec. 31, 1995; and require landlords to request approval from the city before increasing rents more than 100 percent above the Consumer Price Index.

Alameda Measure M1

Limits annual rent increases to 65 percent of the Consumer Price index, prohibits “no-cause” evictions and requires landlords to pay eviction relocation fees ranging from $7,300 to $18,300 when terminating certain tenancies. Creates a rent board and bans evictions without just cause.

Alameda Measure L1

Affirms City Council’s rent stabilization ordinance requiring mediation for rent increases above 5 percent; requires landlords to pay relocation fees when terminating certain tenancies.

Burlingame Measure R

Caps annual rent increases at 100 percent of Consumer Price index. Creates a five-member rental Housing Commission appointed by the City Council and bans “no cause” evictions. Gives relocation fees equal to three months rent.

Richmond Measure L

Caps annual rents at 100 percent of Consumer Price Index. Creates five-member rent board and bans “no cause” evictions.

San Mateo Measure Q

Annual rent increases capped at 100 percent of Consumer Price Index, with a maximum 8 percent increase. Creates a five-person rent board appointed by the City Council, bans “no cause” evictions.

Mountain View Measure V

Annual rent increases limited to between 2 and 5 percent, based on 100 percent of the Consumer Price Index. Prohibits evictions without just cause, creates a Rental Housing Committee to enact regulations.

Mountain View Measure W

Adopts tenant-landlord dispute resolution program and binding arbitration for rent increase disputes exceeding 5 percent of base rent per 12-month period. Prohibits eviction of tenants without just cause or relocation assistance. |

|