I was particularly proud this past week to be a part of a City Council

that was willing, almost unanimously, to actually define the cutting

edge of legislation involving protection from secondhand smoke.

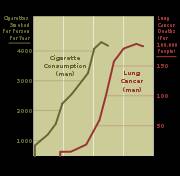

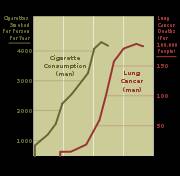

The span of my lifetime also pretty well defines both the dramatic rise

and continuing fall of the acceptance and promotion of tobacco smoking

in the United States. The late 1950s was the high point when 44-47% of

all adult Americans smoked; over 50% of men, and about 33% of women,

following by only a few years a time when the U.S. Government (and

tobacco companies) provided free cigarettes as part of the food ration

to millions of G.I’s.

In the early 1950’s I remember seeing advertising disguised as

documentary films produced by tobacco companies touting the benefits of

smoking actually shown as part of the instructional program in

elementary school.

Most doctors I knew as a youth smoked, and ads in magazines like Life

routinely featured doctors promoting specific brands of cigarettes.

Adults typically smoked at the dinner table after eating or sometimes

even while eating.

Smoking was routine on trains, planes and buses, in restaurants, movie

theaters and workplaces. Even schools and hospitals. Ashtrays were

everywhere, more often than not occupied by a burning cigarette. Smoking

was accepted as a right, and objections to second-hand smoke were

generally perceived as frivolous.

At college, smoking was actually allowed in the classroom subject to

discretion of the professor, which was more often than not granted

because the professor wanted to smoke in class. Informal receptions of

clubs and organizations in college were routinely called “smokers,” and

free cigarettes provided by tobacco companies were often featured.

I grew up in a place where my parents and most other parents smoked, all

day every day – at home and in the car (with the windows rolled up in

winter). Both my parents died from smoking related diseases, my father

from lung cancer and my mother from emphysema.

Although tobacco legislation and studies of health risks began to appear

in the early 20th century, smoking got a huge boost during

the two world wars, and for early 40 years, any anti-smoking activity

was deemed virtually anti-American. It was not until the late 1950s that

health authorities once again began to strongly suggest that there was a

relationship between smoking and cancer. In 1966, the surgeon general

first required the warning “Cigarette Smoking May be Hazardous to Your

Health,“ and in 1971, cigarette advertising on television was banned.

The trend had finally been reversed.

While some advocates of tobacco-related legislation were clearly

interested in saving smokers, the most important motivation has been

saving non-smokers from the discomfort and health-related impacts of

secondhand smoke. Along the way, however, the percentage of American

smokers has declined by over 50%.

In 1995, the “Marlboro Man,” television cowboy, David McLean, died of

lung cancer at 73.

Recent responses to Richmond’s legislation have suggested reprises of

Nazi Germany and invasions of privacy by government. People have

suggested Richmond should be paying less attention to secondhand smoke

and more attention to violence and homicides. As I emailed one critic

this morning:

This was not about protecting you; it was about protecting people who

cannot protect themselves, including children susceptible to asthma and

older people with health conditions that are aggravated by smoke.

As the [Contra Costa Times] article said, " Secondhand smoke is

listed as a human carcinogen by the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency." If people want to kill themselves, that's personal. If they are

putting someone else at risk, them it's a public problem.

The role of government, broadly, speaking, is to protect and enhance

public health, safety and welfare. It is entirely appropriate for

government to take action to limit unwanted exposure to secondhand

smoke.

This is part of a trend that started with transportation, restaurants

and bars and the workplace, all of which have been very successful and

well-received by the overwhelming majority of people.

I hope you reconsider your condemnation.

This is not a right to privacy issue or a private property issue. One

person suggested it should not apply to condominiums because they are

private property. I can tell you as an architect that there is nothing

in the building code that makes a condominium any more smoke-tight

between units than an apartment building. From a building code

standpoint, both are regulated by the same code section and are

considered simply multi-unit dwellings.

As a City Council member, I cannot stop people from killing each other

with guns, just as I can’t and won’t stop people from smoking, but I can

legislate an end to secondhand smoke where if affects vulnerable people

in multi-family dwellings, and it will probably be much easier to

enforce than laws against murder. It may also save just as many lives.

As I have grown older, I have watched with great satisfaction the end of

smoking first in movie theaters and classrooms. Later came planes,

workplaces and then bars and restaurants. These laws were made largely

by someone else, typically state or federal legislators. I am proud that

as a mere city council member, I can take a seat along with these other

pioneers in an increasingly enlightened nation that has wakened to the

dangers of secondhand smoke and taken action to protect those who can’t

protect themselves. In the process, America has become healthier.

From today’s West County Times:

Richmond tightens smoking rules

By Katherine Tam

West County Times

Posted: 07/11/2009 12:45:52 PM PDT

Updated: 07/12/2009 05:26:01 AM PDT

Richmond will ban smoking in apartments and

condominiums in addition to public places, making the city the toughest

place in the Bay Area to light up.

City officials will require multiunit housing to go smoke-free by

Jan. 1, 2011. That includes individual apartment units and common areas

such as lobbies and patios, where experts say secondhand smoke can seep

through cracks, vents and wall sockets. Apartment owners can designate a

smoking area, but it must be at least 25 feet away from where smoking is

prohibited.

Fines for violating the new ban on smoking in multiunit housing start

at $100.

The new ordinance, which the City Council approved this month, is on

top of additional regulations created in May that bar smoking in public

places such as parks, trails and where parades, farmers markets and

other public events are held. Smoking is prohibited indoors where people

congregate and work — regardless of whether it's publicly or privately

owned — including restaurants, bars and conference rooms.

That's a big change from more than a decade ago when people hoping to

keep secondhand smoke at bay created smoking and nonsmoking sections in

restaurants and airplanes.

"We're on the right side of history," Councilman Tom Butt said. "This

idea that somehow you could bifurcate buildings and make portions of it

smoking, portions of it nonsmoking, it just doesn't work."

Richmond now has on the books the strictest batch of secondhand

smoking laws in the region, said Serena Chen, a regional director at the

American Lung Association in California. Other cities have some of the

same laws, but not all of them.

Secondhand smoke is listed as a human carcinogen by the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency.

It was an F grade on an American Lung Association report card in

January that spurred Richmond officials to toughen their laws. That

report card graded cities on how well they discouraged smoking by

developing laws that ban smoking outdoors and in multiunit housing and

that regulate tobacco sales.

Most cities in the Bay Area got a D or F. No one got an A; five

jurisdictions — Contra Costa County, Oakland, Berkeley, Novato and

Belmont — got Bs.

Belmont made national headlines in 2007 when it became the first in

the country to ban smoking in multiunit housing; that went into effect

in January. Dublin followed suit in 2008 with a less-restrictive

requirement that half the units in buildings with more than 16 rentals

be smoke-free by 2010.

In Richmond, people can continue to smoke at home if it is a

single-family house and on sidewalks and streets, but not within 25 feet

of a door, window or vent that leads to a place where smoking is

prohibited. Tobacco retailers are required to get a permit.

Smoke-free law supporters celebrated with hugs in the back of the

City Council chamber this past week after officials passed its latest

law. Smokers and apartment representatives, who were fewer in number at

the meeting, were less enthused. Theresa Karr, who represents the

California Apartment Association, asked the city to cushion the

financial blow to apartment owners and tenants by requiring half,

instead of all, the units in existing buildings be smoke-free. Evictions

could be an unintended consequence, she warned.

"You are not only financially impacting owners and operators of

rental properties, you're probably going to financially impact tenants

who maybe have no other bad habit other than they smoke," Karr said. |